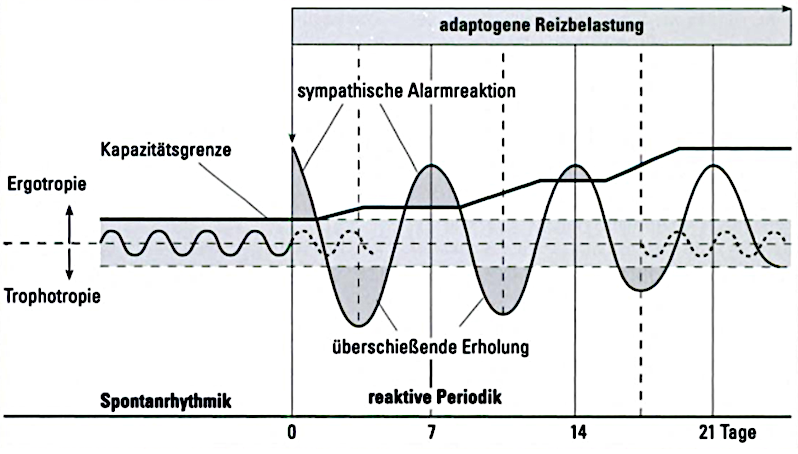

Fig. 4 - Schematic representation of the triggering of reactive periodicity by adaptogenic stimulation (according to Hildebrandt, 1985 as cited in Melchart, 2002, p. 35)

The cortical organisation also carries out adaptation processes, in particular by avoiding negative self-evaluation, defending against external threats and down-regulating stressful impulses.

Training body awareness (breathing therapy, relaxation techniques) and focussing on mindfulness exercises increase the ability to focus attention on self-perception as a whole and to better understand and accept body signals. This can result in a more conscious way of dealing with oneself and thus an increased health awareness.

Psychological resilience is made up of three main components:

- An inner attitude of being able to cope with life despite adverse circumstances

- Recognising stressful events as a challenge to develop

- Developing the ability to recognise oneself as part of life

This is also where cognitive therapies to increase stress resistance come in.

For the ordering therapy of naturopathy, impulses for autoregulatory cognitive work are therefore just as relevant as the (re)ordering of life goals. They are basically elementary for any sensitive communication in the practitioner-patient situation.