Introduction

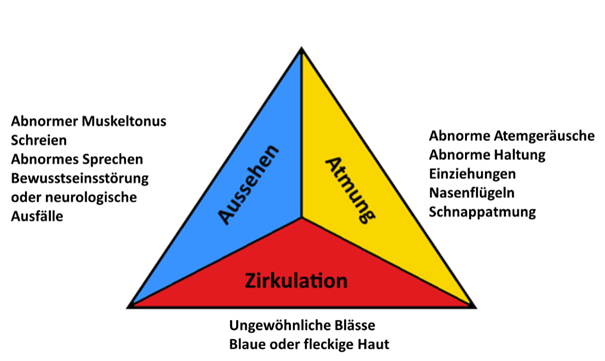

Fever is one of the most common phenomena in children that doctors and alternative practitioners are confronted with, although it is rarely caused by a serious illness. Given the often considerable concerns of parents (especially with their first child), advising parents, examining the child and making a differential diagnosis requires a great deal of sensitivity, diagnostic competence and knowledge of the so-called "red flags" for recognising a "potentially dangerous condition (PDC)".

The first guideline on fever management in children and adolescents issued by the Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften, AWMF) now provides important guidance (see: https://register.awmf.org/de/leitlinien/detail/027-074

Fortunately, the recommendations mark a departure from the long-standing medical tradition of rapid fever reduction and teach a relaxed approach to this symptom, which in most cases is a natural reaction of the organism. The guideline representative of the German Society for Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine (Deutschen Gesellschaft für Kinder und Jugendliche DGKJ) says:

"The new guideline emphasises a fundamentally changed understanding of fever: it is not considered a symptom that requires priority treatment, but rather a physiological and usually helpful defence reaction of the body." (Prof. Dr Tim Niehues, German Society for Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine e. V. 2025; transl. by the author)

The following section provides a detailed overview of the key content of the new guideline on fever management in children and adolescents.