[1] For experience shows "[...] that the smallest quantity of mercury, if it only excites a duly strong mercurial fever, can raise the highest degree of the most ingrained epidemic of lust". [Trans. by the author](Hahnemann, 1789, p.188f.)

[2] Hahnemann was in Leipzig and Vienna from 1775-1777 to study medicine; from 1777-1778 as librarian and personal physician to Baron von Brukenthal in Hermannstadt (Transylvania), where Hahnemann must have contracted an infection with the malaria endemic there; from 1778-1779 doctorate in Erlangen.

[3] Although microbes as pathogens could not yet be detected and made visible in Hahnemann's time, the term "contagion" had long been used in medicine. It is based on the observation that someone developed the same signs of illness after contact with a sick person. The Italian physician Girolamo Frascatoro (1478-1553) had already developed a theory of contagion as an explanatory model for the development and spread of epidemic diseases, but it was forgotten again. Luther (1483-1546) also used the term: "... especially the poison of a contagious disease, the contagion and the plague itself: the enemy has sent in gifft and deadly geschmeis to us through gottes verhengnis. Luther 3, 396b". By the 18th century at the latest, the term contagion was in general use in connection with the fight against smallpox and venereal diseases.

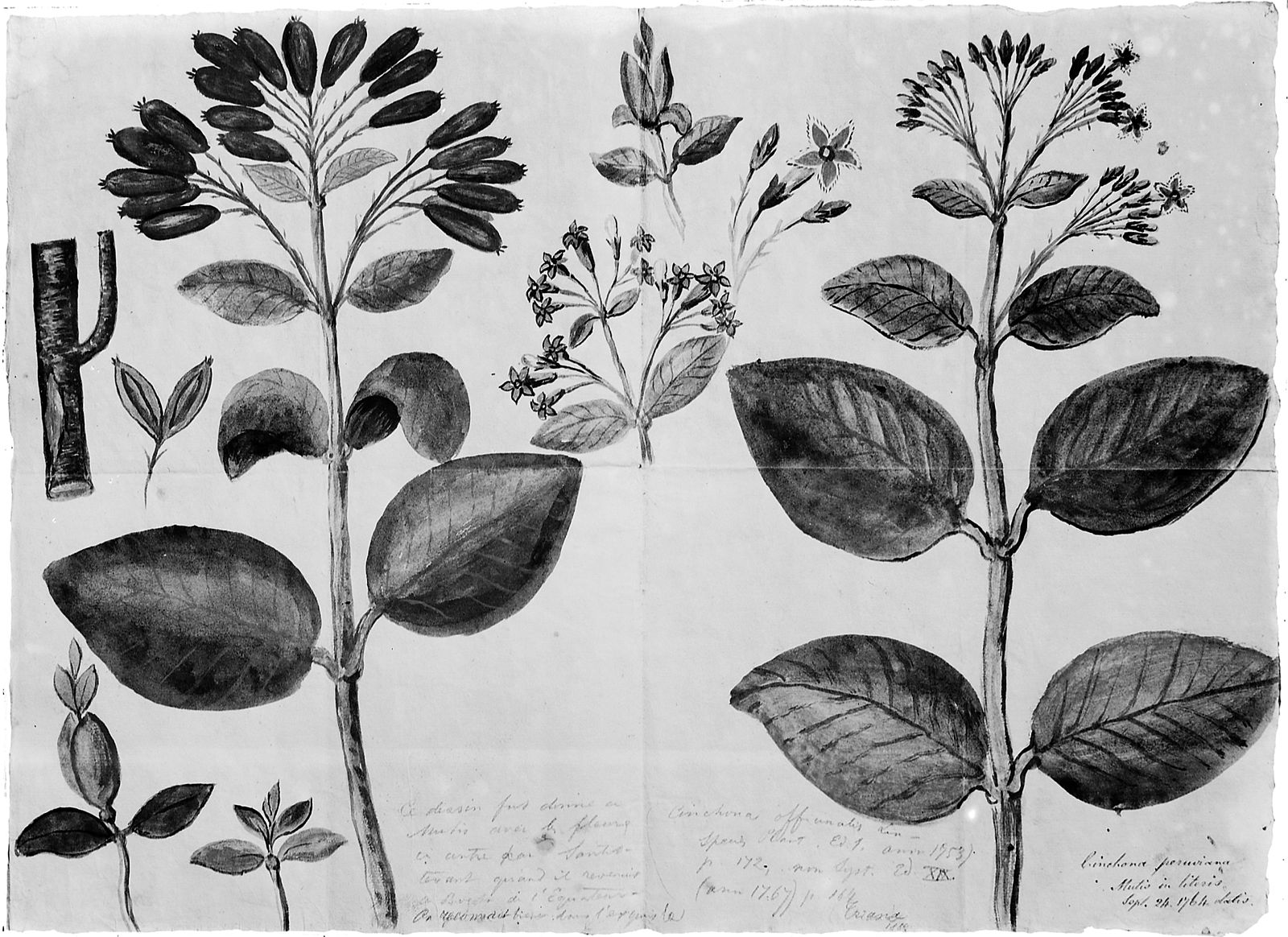

[4] "For how else could it be possible that the violent three-day and daily fever, which I cured four and six weeks ago, without knowing how it happened, with a few drops of tincture of quinine without afterpains, had almost exactly the series of coincidences which I perceive in myself yesterday and today, since I have, healthily, gradually taken four quarts of good quinine bark, for the sake of experiment!" [Trans. by the author] (Hahnemann, 1808, p. 494)

Literature

[1] Lochbrunner, Birgit (2007): Der Chinarindenversuch – Schlüsselexperiment für die Homöopathie?, Essen: KVC Verlag.

[2] Hahnemann, Samuel (1789): Unterricht für Wundärzte über die venerischen Krankheiten, nebst einem neuen Queksilberpräparate. Leipzig: Siegfried-Lebrecht Crusius.

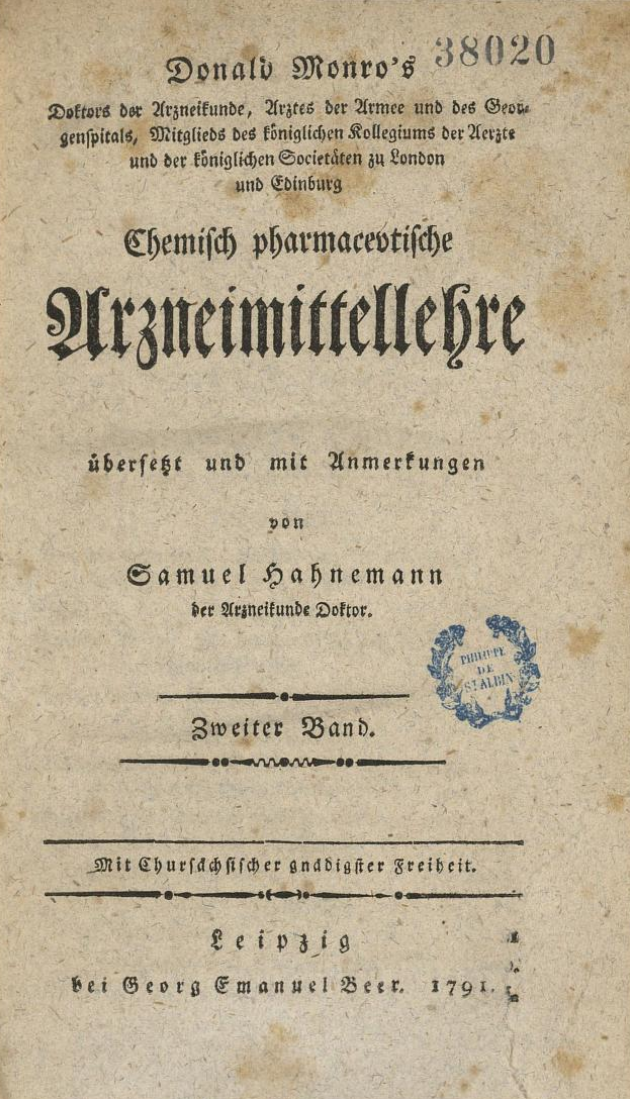

[3] Hahnemann, Samuel (1791): Donald Monro's, Doktors der Arzneikunde, Chemisch pharmaceutische Arzneimittellehre welche die Londner Pharmacopöe praktisch erläutert - übersetzt und mit Anmerkungen von Samuel Hahnemann. Leipzig: Georg Emanuel Beer.

[4] Hahnemann, Samuel (1792): Verwahrung vor Ansteckung in epidemischen Krankheiten; Freund der Gesundheit, Bd.1, Heft 1. Frankfurt am Main: Wilhelm Fleischer.

[5] Hahnemann, Samuel (1805): Heilkunde der Erfahrung; Hufeland's Journal der practischen Heilkunde, Band 22, 3. Stück, S.5-100. Berlin: Wittich.

[6] Hahnemann, Samuel (1807): Fingerzeige auf den homöopathischen Gebrauch der Arzneien in der bisherigen Praxis; Hufeland's Journal der practischen Arzneykunde, 26. Band, 2. Stück, S. 5-43. Berlin: Wittich.

[7] Hahnemann, Samuel (2001): Gesammelte kleine Schriften; Auszug eines Briefs an einen Arzt von hohem Range, über die höchst nöthige Wiedergeburt der Heilkunde (geschrieben 1808, veröfffentlicht im Allg. Anzeiger der Deutschen, 343, S.3729-3741). Hrsg. v. Josef M. Schmidt u. Daniel Kaiser. Haug. Download available under https://zs.thulb.uni-jena.de/rsc/viewer/jportal_derivate_00263172/Reichsanzeiger_167367196_1808_02_0001.tif (8.6.2023)

[8] Hahnemann, Samuel (1796): Versuch über ein neues Prinzip zur Auffindung der Heilkräfte der Arzneisubstanzen; Journal der practischen Arzneykunde und Wundarzneykunst: hrsg. von C. W. Hufeland, 1796, 2. Band, 3. Stück S. 391-439 und 4. Stück S. 465-561. Jena: in der academischen Buchhandlung.